If you’ve never prepared a medical device FDA premarket notification, commonly known as a 510(k) submission, figuring out where to begin can be daunting. The FDA website provides a goldmine of information but extracting those golden nuggets requires lots of digging. Fear not. This guide removes much of the confusion about the topic and after reading it you’ll have a much better understanding of how the 510(k) process works.

In this article:

Basic steps in the premarket notification process

Confirm that your medical device needs a 510(k)

Identify the right product code and regulation number

Choosing the right predicate device

Do you have the data needed to support a submission?

FDA 510(k) submission checklist

Sifting through guidance documents and standards

Do We Have to Follow FDA Medical Device Guidance Documents?

What to expect after you submit your 510(k) application

Sections of a 510(k) application

Be prepared for additional information (AI) requests

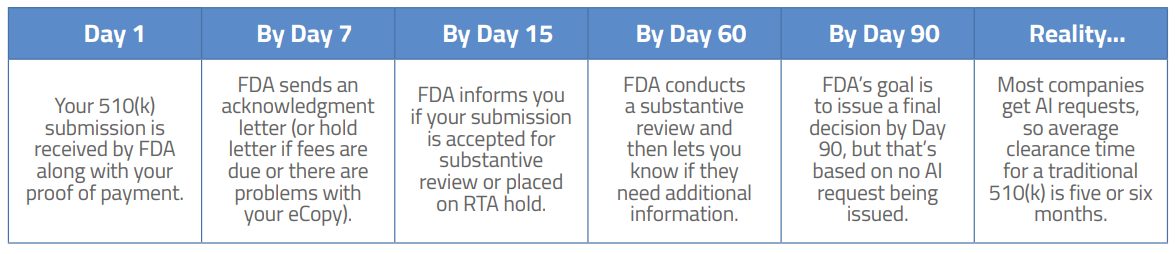

Typical FDA 510(k) review cycle

We’ll explain various steps in the process throughout this guide, but let’s start with a holistic review of the FDA approval process.

1 | Confirm classification of your medical device and whether it falls under the 510(k) pathway. |

2 | Using the FDA website, identify the appropriate three-letter product code and regulation number for your device. 3. Determine whether your device can be submitted under a Traditional, Special or Abbreviated Pathway |

3 | Conduct research on the FDA database and select a predicate for comparison or if you will use recognized consensus standards and guidances to establish substantial equivalence. |

4 | Search on the FDA website for applicable FDA guidance documents. |

5 | Determine which international “consensus standards” may apply to your device. |

6 | Identify clinical data and/or testing that may be required for your device. |

7 | Complete performance testing and perform clinical studies (if required). |

8 | Assemble all documentation into the 510(k) application. |

9 | Review the Refuse to Accept (RTA) checklist to ensure that you’re following the FDA guidelines for completeness. |

10 | Complete the User Fee Coversheet and pay the 510(k) review user fee and include the coversheet in the 510(k) submission to FDA. |

11 | Receive confirmation from FDA within 2 weeks that your 510(k) was accepted for substantive review. |

12 | If your 510(k) is determined to be substantially equivalent, you will receive a clearance letter that will be posted on the FDA website. Within 30 days of placing the device on the market, you must list it on the Device Registration Listing Module (DRLM) and pay the Device Listing Fee. |

The FDA will not issue a certificate or letter approving the new device. We should note that FDA does not technically “approve” devices via the 510(k) process – they “clear” (authorize) a device to be marketed in the US. That’s why a 510(k) is called a premarket notification .

This may seem obvious, but the very first step is to confirm that your product is a regulated medical device and needs to go through the 510(k) approval process. Some products (i.e., low-risk devices Class I products) do need to be registered with FDA but don’t need to go through the FDA 510(k) process. Nearly all Class II devices must procure a 510(k). Following is information on how you can find out whether your device is regulated and needs a 510(k).

FDA uses a risk-based predicate-based review approach. This means that when you submit your application to FDA, you will be comparing your medical device to a very similar device that has already been approved (the predicate) by FDA. Because FDA requires you to identify a single predicate device, your first step will be to find one. You may already have a good idea of which competitive products would make a suitable predicate for comparison in your 510(k). In any case, you should start your research using the FDA Product Classification database.

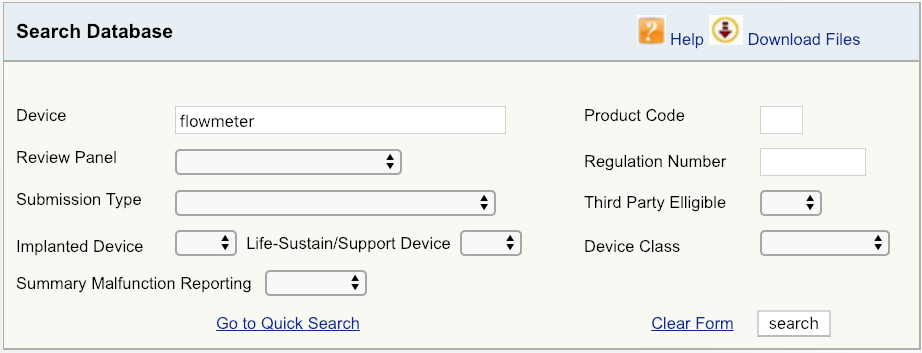

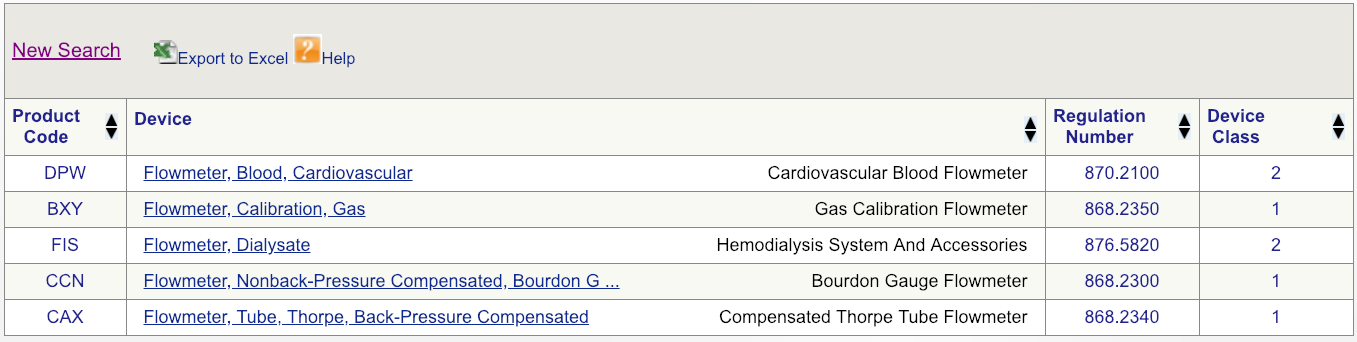

For example, let’s say your company is introducing a new cardiovascular blood flowmeter to the US market. The first step would be to begin with a simple device search on the FDA database, as shown, and then look at the options available. Start with broadest definition of your product – in this case, just the term “flowmeter.” The results show that there are six unique FDA product codes for products related to flowmeter.

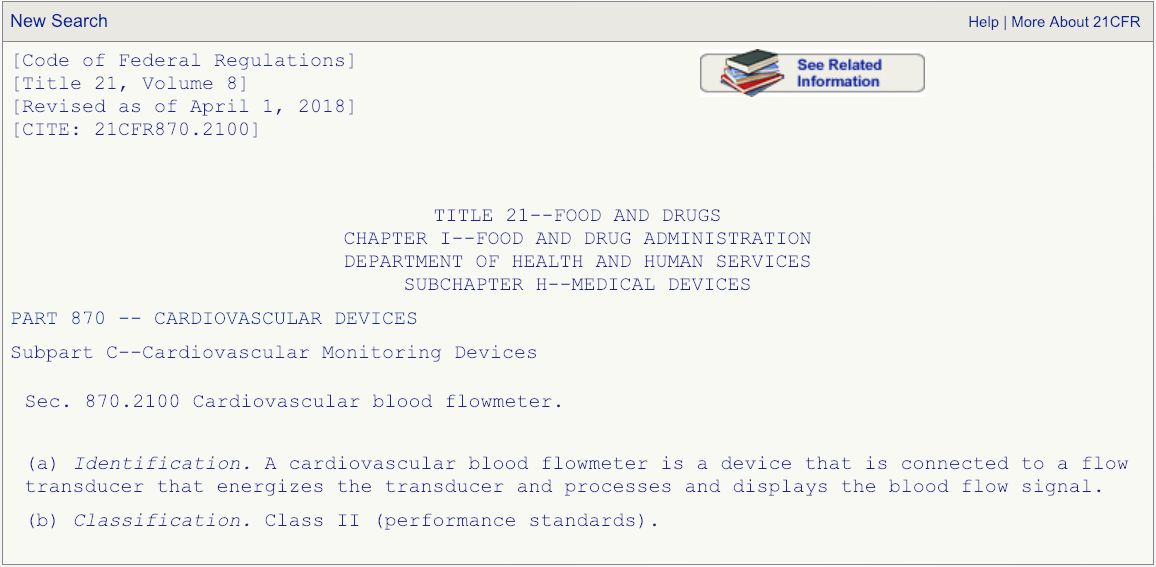

Code DPW looks to be the best match but, to make sure, click on the regulation number and carefully read the description.

After you have read the description associated with the regulation number and are absolutely certain that the product code DPW is the correct one that fits your device, then go the FDA’s 510(k) database and search for any devices cleared under product code DPW.

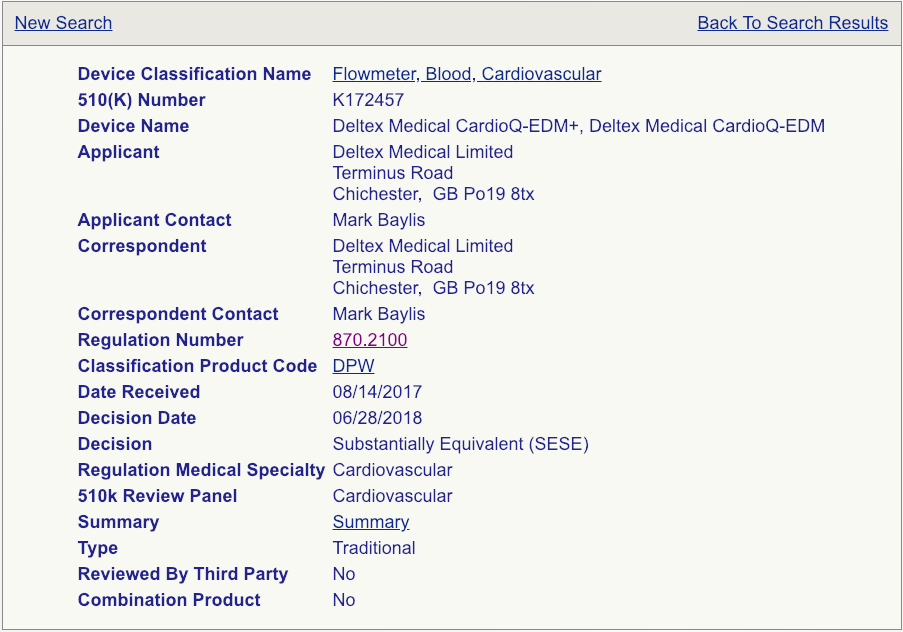

This is where things can get tricky and you need to be careful. In this example, there are 131 cleared medical devices under classification product code DPW. Which one will make the best predicate for your device? Well, here’s a piece of advice: When reviewing your options (hopefully you will not have 131 options), it is best to sort by the “Decision Date” column and start with devices that were cleared recently. Why? While it may be tempting to choose an older device as your comparative predicate, the FDA frowns upon using devices cleared more than 10 years ago.

Your next step will be to click on the “Summary” link for each device as shown (see the example page below).

Read these summaries very, very carefully. Pay attention to the intended use, allowed indications for use, testing conducted, and clinical studies that may have been performed. Some 510(k) summaries provide more information than others, so make sure you review as many as possible and aggregate your knowledge in a spreadsheet if you are reviewing a lot of summaries. Your chosen predicate does not need to be identical to your device, but it needs to be close enough not to raise additional safety and effectiveness questions. The chosen predicate must have the same intended use and indications for use. This is very important. If the indications for use are different, that device won’t be a suitable predicate. The technological features should closely match your device. Choosing the right predicate is truly critical for the success of your submission and, if you have any reservations about your options, you should seek the advice of an experienced FDA consultant.

A limitation of the FDA predicate registration system is that it does not easily accommodate innovation. In the past, this was why some companies introducing innovative technology chose to introduce their devices to the European market first. If you have truly new technology or your device combines two existing technologies, you can ask FDA to render an opinion on the classification and regulatory requirements for the device by submitting a 513(g) request for information. Some companies making innovative low-risk medical devices without a suitable predicate device can go through the De Novo process. This allows FDA to assign a Class I or Class II designation and product code/regulation number to a product that has no current relevant product code.

You may also request a Q-Submission Meeting (Q Sub) with FDA to clarify regulatory requirements, get advice on what technical documentation to include, or discuss clinical studies needed to support your submission. These short meetings (in person, via phone, or in writing) allow you to ask a few substantive questions (depending on time allowed) and can be a worthwhile way to ensure that you don’t waste time and money. Unless you are absolutely confident of the path you need to take and what will be required in your submission, we recommend taking advantage of a Q-Sub meeting. (We can help you with this.) Nearly two-thirds of all FDA 510(k) submissions are slowed down by Additional Information (AI) requests from FDA reviewers. We’ll talk more about AI requests later.

So you’ve done your homework and confirmed that your device must go through the 510(k) process. You know the classification, three-letter product code, and the regulation number, and you’ve done an exhaustive review of summary documents for competing devices. You have chosen your predicate medical device and are ready proceed. Now what?

If you have never seen a completed 510(k) before, you might be shocked to know that the average submission is nearly 1,200 pages. Many people vastly underestimate the work that goes into a submission, so it’s probably not surprising that FDA reviewers initially reject about 30% of all submissions as being incomplete. Several years ago, FDA adopted a Refuse to Accept (RTA) policy to cut down on the time they were wasting reviewing woefully inadequate submissions from medical device companies. Now FDA uses a 50+ point review checklist before accepting any 510(k) for substantive review. You can read the FDA 510(k) acceptance criteria hereut provides great information, and you should study it carefully before starting your 510(k). 180 days to rectify the shortcomings and submit information against the deficiencies.

The next step in the process is determining which data is needed to support your submission. Generally, that supporting safety and efficacy data falls into four buckets.

1 – Bench testing (performance, biocompatibility, electrical safety, sterilization, packaging, sterility, etc.

2 – Clinical studies

3 – Usability studies

4 – Software validation and verification (if applicable)

If you have done a good job of reading various 510(k) summaries for your competitors, you should already have an idea of what data may be required. Let’s use the example of a cardiovascular blood flowmeter and focus on FDA guidance documents first. If you do a quick search of FDA guidance documents and sort using “Medical Devices” and “Cardiovascular Devices,” you will find no fewer than 21 guidance documents. Does your device include software? There are another eight guidance documents related to software and cybersecurity. Will all of these guidance documents apply to this cardiovascular blood flowmeter device? Absolutely not, but it is your unenviable job to read through them and determine which ones do apply. Again, if you have done a thorough job reviewing a lot of possible predicate devices, you’ll likely see commonality in which specific testing was performed or standards followed.

It should be noted that in addition to the 700+ FDA medical device guidance documents, FDA also recommends the application of international “consensus standards” in many cases. One common example is the IEC 60601 series of electrical safety standards, and the ISO 14971 standard for risk management. The IEC 60601-1 series of standards is for general safety and performance, while the IEC 60601-2-x series applies to specific medical equipment.

Again, as you review possible predicate devices and read their 510(k) summary documents posted on the FDA website, you will discover that many companies disclose the specific testing that was conducted on their product. For example, with regard to the cardiovascular blood flowmeter mentioned earlier, one manufacturer listed the tests performed on their device in their 510(k) summary:

Of course, there are many companies that specialize in performing medical device testing, and you will also want to confer with them and triangulate which specific testing will be needed for your device. Just keep in mind that their job is to sell testing. Trust but verify….

Technically no, but guidance documents reflect current FDA thinking on a topic, so you would be foolish to ignore them. However, be prepared to substantiate with a scientifically justified alternative for any deviations from the published guidance or else you will receive a request for Additional Information (AI) during the review of the 510k. In fact, during the RTA checklist review, FDA reviewers will often cite specific references to guidance documents if the company has not applied them. You will run across many “draft” guidance documents in the FDA database, some going as far back as 2007. The word draft is a bit of a misnomer, because people erroneously assume these draft documents are not yet being applied by FDA. However, draft guidance documents are really early versions of guidance documents about which the FDA is still accepting industry feedback. Guidance documents often remain in draft format for many years but are applied during this time.

Keep in mind that FDA does also withdraw guidance documents, so when you are reviewing 510(k) summaries for predicate devices or doing other research and you see specific guidance mentioned, make sure the guidance in question is still in effect. Here’s a list of withdrawn CDRH guidance documents.

FDA does not publish a specific template for the 510(k) application, but they do want you to organize your submission into 20 specific sections. Sections 14-20 may not be applicable, depending on your device. While there is no specific template to follow, FDA does provide a thorough overview of what is expected in each section know more – you should start by reading this page, as it contains links to numerous other guidance documents that pertain to each section.

1 | Medical Device User Fee Cover Sheet (Form FDA 3601) |

2 | CDRH Premarket Review Submission Cover Sheet |

3 | 510(k) Cover Letter |

4 | Indications for Use Statement |

5 | 510(k) Summary or 510(k) Statement |

6 | Truthful and Accuracy Statement |

7 | Class III Summary and Certification |

8 | Financial Certification or Disclosure Statement |

9 | Declarations of Conformity and Summary Reports |

10 | Executive Summary |

11 | Device Description |

12 | Substantial Equivalence Discussion |

13 | Proposed Labeling |

14 | Sterilization and Shelf Life |

15 | Biocompatibility |

16 | Software |

17 | Electromagnetic Compatibility and Electrical Safety |

18 | Performance Testing—Bench |

19 | Performance Testing—Animal |

20 | Performance Testing—Clinical |

As we mentioned before, the average 510(k) submission is 1,200 pages long! These days FDA reviewers spend about twice as much time reviewing each submission as they did 15 years ago, and much of that increased scrutiny is directed at specific testing and clinical results found in sections 14-20. Also, in the past FDA might have assigned one reviewer to a 510(k) but today several reviewers are involved, including specialists in biocompatibility, electrical safety, and risk management.

When you submit your 510(k) to FDA, the first hurdle is to have it accepted for substantive review. If your submission does not pass FDA’s 50+ point checklist, they will kick it back to you. You certainly don’t want that to happen when you’ve spent months preparing your 510(k), double-checking all details, and following all FDA guidance documents.

Theoretically, in less than three months you should have a clearance letter from FDA in hand and a pat on the back from your boss. But don’t uncork the champagne just yet – nearly two-thirds of all premarket notification submissions receive an ego-deflating Additional Information (AI) request from FDA. For minor issues, this could take the form of a simple phone call from the FDA reviewer (Interactive Review), but for more substantial questions an AI letter will be issued. Common issues that spur an AI request include:

Also, despite the bounty of information published by FDA, sometimes a reviewer asks for information that may not have been published in any FDA guidance document or standard. This does happen and, if it happens to your submission, you will need to deal with it. If an AI request is submitted to your firm, your submission is placed on hold for up to 180 days (just as with the RTA discussed above). If you are unable to supply the requested information within that timeframe, your 510(k) submission may be withdrawn or cancelled, which means you will need to submit again…and pay the review fee again. That’s not a discussion you want to have with your boss during your weekly update.

Plan on six months from the hopeful day you submit until the joyous occasion when you are holding that “substantial equivalence” letter in your hand. In all fairness, because such a high percentage of companies receive additional information requests from FDA, the amount of total time that FDA spends reviewing your submission is only slightly longer than the amount of time companies spend replying to FDA requests. The average time to clearance is around five or six months but that also varies by device.

It can be the most soul-crushing letter any regulatory professional could receive: the dreaded not substantially equivalent (NSE) letter from FDA. While thousands of submissions get blessed by FDA each year, hundreds don’t make the cut. Even if devices accepted for substantive FDA review and their sponsors reply to AI requests, some of the applications get rejected. Why? Typically, an NSE letter is issued because no matching predicate exists, the device has a different intended use, the device has different technological characteristics, or performance testing does not support safety and efficacy of the device. If a device is rejected because no predicate exists, companies may be able to request a risk-based classification from FDA via a De Novo petition.

In addition to the applications that are rejected, hundreds more are abandoned (withdrawn) because the sponsor of the 510(k) could not produce the necessary testing or data requested in the AI letter.

Luckily most companies do not get NSE letters. The substantially equivalent (SE) letter is not an approval by FDA, but it serves the same purpose because it legally authorizes the holder to market the device in the US. Unlike other countries, no certificate will be issued by FDA but your SE letter will be posted on the FDA website along with your 510(k) summary. Your 510(k) clearance will not expire and is valid until you make changes to the intended use, alter the indications for use, or change technological characteristics. At the time your 510(k) clearance letter is issued, you are expected to be in full compliance with the FDA Quality System Regulation (21 CFR Part 820) when distribution of the device begins in the US.

Getting FDA clearance for a medical device is a lot of work and a huge accomplishment. If you spend time doing your homework, you can be assured that your path to 510(k) success will be shorter, smoother, and more likely to result in you securing the coveted substantially equivalent letter.

We hope you have enjoyed this guide to the FDA 510(k) process. If you are getting ready to start your first 510(k), consider our training class on FDA and European regulatory submissions. Also, our team of FDA experts is available to help you with 510(k) strategy, review, or compilation.

US OfficeWashington DC

EU OfficeCork, Ireland

UNITED STATES

1055 Thomas Jefferson St. NW

Suite 304

Washington, DC 20007

Phone: 1.800.472.6477

EUROPE

4 Emmet House, Barrack Square

Ballincollig

Cork, Ireland

Phone: +353 21 212 8530